These are some of the key questions raised by architect, writer, and researcher Alina Paias, curator of the exhibition Taking More Than What’s There to Give at Prague’s VI PER Gallery. In the show, she relates them to architecture and construction, to their interventions into landscapes as well as into individual human lives—convinced that “when it comes to conventional practice, making architecture still means relying on different forms of extraction.” The exhibition is supported by the international platform LINA, which connects institutions and creators working across architecture and related fields in favor of regenerative practices. VI PER Gallery is the only Czech member of this network, and thanks to it the exhibition is also presented in parallel as part of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale.

Taking More Than What’s There to Give brings together a wide spectrum of projects—from the environmental history of modern glass architecture, to maps of Atlantic Forest deforestation, to post-apocalyptic photographs of an unfinished port. The exhibition’s very installation also comments on the use of energy: the Dutch studio Netherlands Angry Architects references the issue symbolically by printing the display panels on a thermal printer. The decision to use this energy-saving technology amplifies their statement. In the monochromatic space, lit by soft daylight, the black-and-white directness of the text stands out.

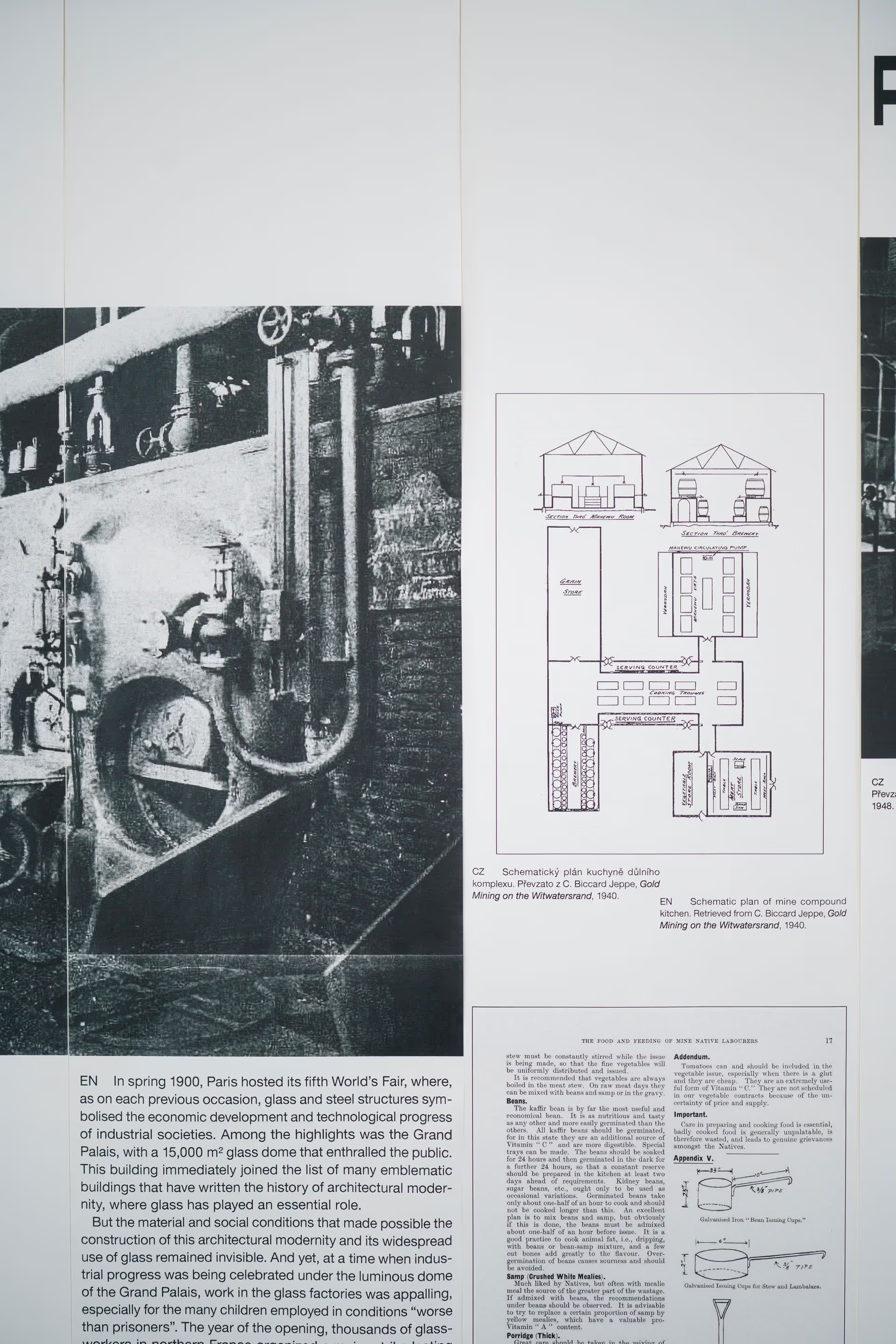

Not all of the research projects, however, focus exclusively on natural resources — an equally central aspect of the curatorial scope is pointing out unethical forms of exploiting human labor as yet another type of extraction. One of the works addressing this issue is a study by the Belgian architectural collective BAU (Belgian Architects United), which, through graphs, personal testimonies, and even memes, presents an analysis of the common precarization practices within architectural offices. Far from being specific to Belgium, these issues may resonate with painful familiarity in the Czech context.

Most of the exhibited works intertwine questions of societal and community impact, whether on a local or global scale. Yet an even stronger unifying thread is the heavy, depressive undertone that permeates the entire exhibition, leaving behind a lingering aftertaste of hopelessness.

One project deserves special attention for its direct relevance to a European audience: research by Dutch-Ukrainian architect Lesia Topolnyk. Her New Ecological Order explores the often-overlooked ambivalence of so-called sustainable energy sources, using the example of Morocco’s solar power plant—operated by an international corporation and exporting energy to European markets. As the largest concentrated solar facility in existence, the plant severely disrupts local ecosystems through the sheer scale of land occupation, while also undermining the lives of the Berber community. Residents are often forced to leave their homes, altering traditional land use and livelihoods. The project critically highlights power relations that, in many ways, echo the mechanisms of fossil fuel politics.

If we aim for a more sustainable future, we must carefully consider all the impacts of this transition. The exhibition makes a convincing case that even well-intentioned efforts—such as Europe’s shift to renewable resources—can carry unsettling echoes of colonial practices from past centuries. It is essential to draw attention to problematic approaches that persist in the present. Seeing reality in all its complexity is key. At the same time, we must ensure that the anxiety of our current condition does not harden into resignation.

The exhibition Taking More Than What’s There to Give is on view at VI PER Gallery in Karlín until April 12.

Adéla Ševčíková (*1999) is a student of Theory and History of Art at UMPRUM in Prague.