Linda, what role does self-sufficiency play in your life and your work? What has your path toward it been like?

My journey toward self-sufficiency was very natural and quite fast — I dove into it headfirst. In 2019, while studying at UMPRUM in Prague, I started to feel weary of city life. The fast-paced lifestyle wore me down, and then with the pandemic, everything suddenly stopped. At that moment, I realized I needed a change. So I returned home to the countryside and took over the family farm — though I started doing things my own way.

In that sense, it was a natural process. Life in the countryside leads me to self-sufficiency every day: suddenly I was surrounded by all the necessary resources, whether food or materials for making furniture. As a result, I try to use every resource to its fullest and to buy as little as possible.

This self-sufficiency has imprinted itself in your creative work as well. The wool you use comes from your own flock. Your role as a designer or textile maker thus expanded into that of a shepherd. How did that journey unfold?

I began with the flock inherited from my parents — a mix of breeds, mostly crossbreeds. Now I keep a small flock of Merinolandschaf sheep, a Central European branch of the original Merino sheep from Spain, from where they spread across the world. Merinolandschaf are large-framed animals that provide both meat and fine wool. But they require quality nutrition, eat a lot, and need plenty of space.

I grew up on a farm, so this environment isn’t new to me, but now that I carry full responsibility, it’s of course different. I constantly plan three-quarters of a year ahead, always thinking about what could be improved to make the daily work easier — because working with animals means every single day, no vacations. I’m still learning how to keep animals in a way that makes them content — it’s a process for a lifetime.

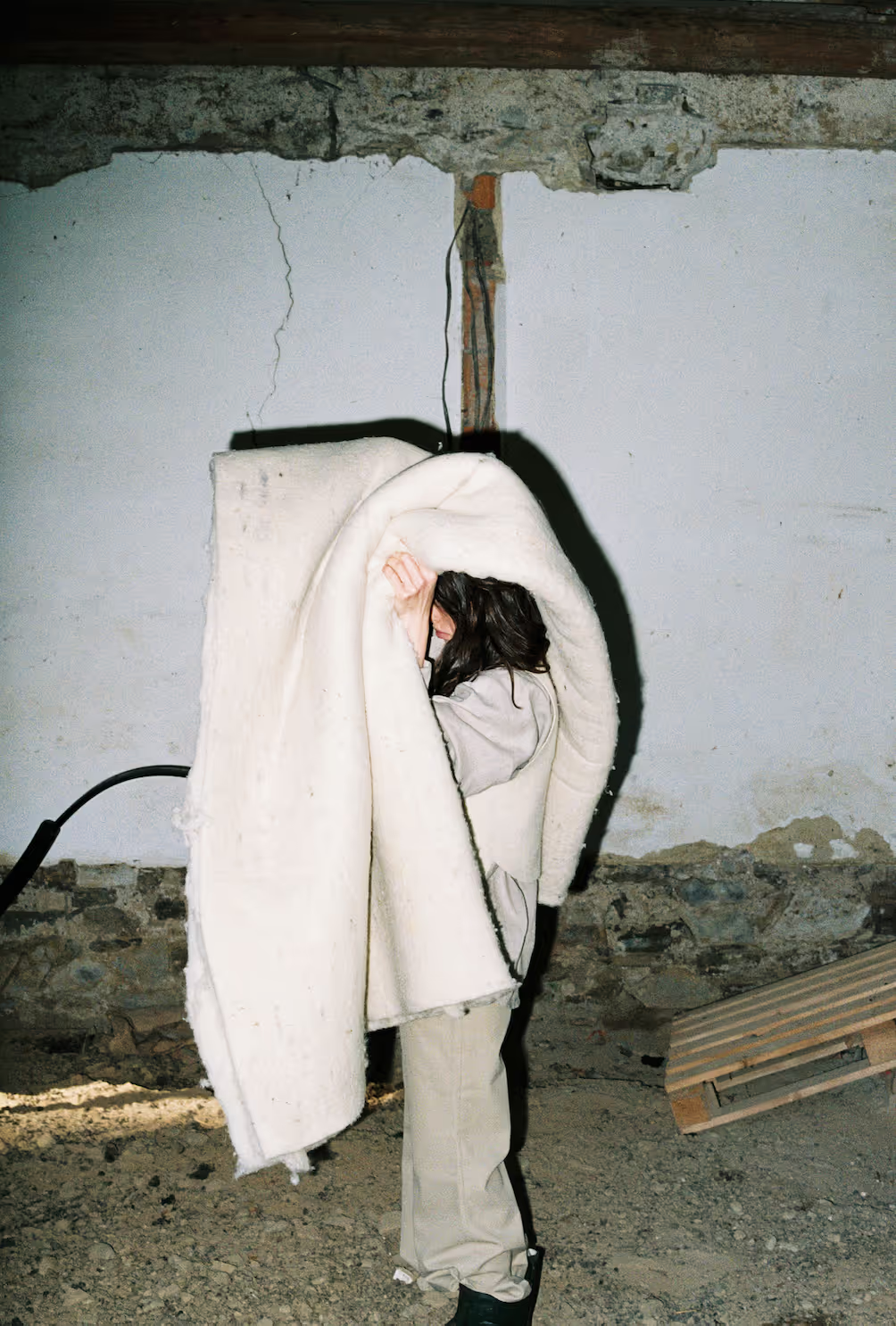

Thanks to farming, you’re present at every step of wool processing, and you also sew the garments yourself. How does that affect your work, and what does the process look like?

We all know Merino wool and the functional products made from it. Today it’s widely promoted as an excellent natural material — but I follow a different process.

I’m interested in purity in wool processing, yet also in dialogue with industrial production. The resulting fabrics are different, because industrial Merino processing involves chemical treatments that damage the fiber — it’s coated with residues from chemical baths. Somewhere inside the final garment there is still wool, but many of its valuable natural properties are lost.

In my work I try to preserve pure processes, even when working within industrial conditions. That’s very challenging, because without chemicals, production technologies behave differently. At the moment, for example, I’m struggling with seams — on the garments they all twist, and no one involved in production can figure out why.

Another difference is that everything I make is fully local. That was a big challenge — finding suitable facilities is difficult today. Few weaving mills survive, as most weaving, washing, and finishing factories disappeared after 1989. So now machines are scarce, opportunities are limited — but I work with what I can find.

What has direct contact with wool production taught you?

One big lesson was realizing just how incredibly demanding the process is — financially and time-wise. Nothing can be rushed. Even shearing has to account for the weather, to get the wool in the best possible quality. Processing wool has many stages, and as I mentioned, the factories are scattered across the country. I have to transport bales between facilities, which prolongs production.

How does seasonality shape your work throughout the year?

Winter is a quiet time — it’s too cold to do much outside, your hands freeze — but I still go to the animals every two hours to feed them. Once I build a proper feeder for my cow, I’ll be able to feed just once a day.

In February comes lambing season, and as a shepherd I can’t help but be there constantly, watching over the ewes. Spring awakens everything, including me: that’s when outdoor work begins — fixing fences and buildings, planting vegetables and potatoes.

Summer is all about haymaking, to prepare enough feed for winter. For me it’s also the season of preserving — canning fruit and vegetables, making jarred mixes, drying herbs and teas. Autumn continues with harvesting and storing produce in the cellar. All this is on top of the daily care — feeding, tending animals. I try to rely as much as possible on my own resources, buying very little, both for myself and the animals.

When we speak about circularity in textile production, can we relate it to natural processes?

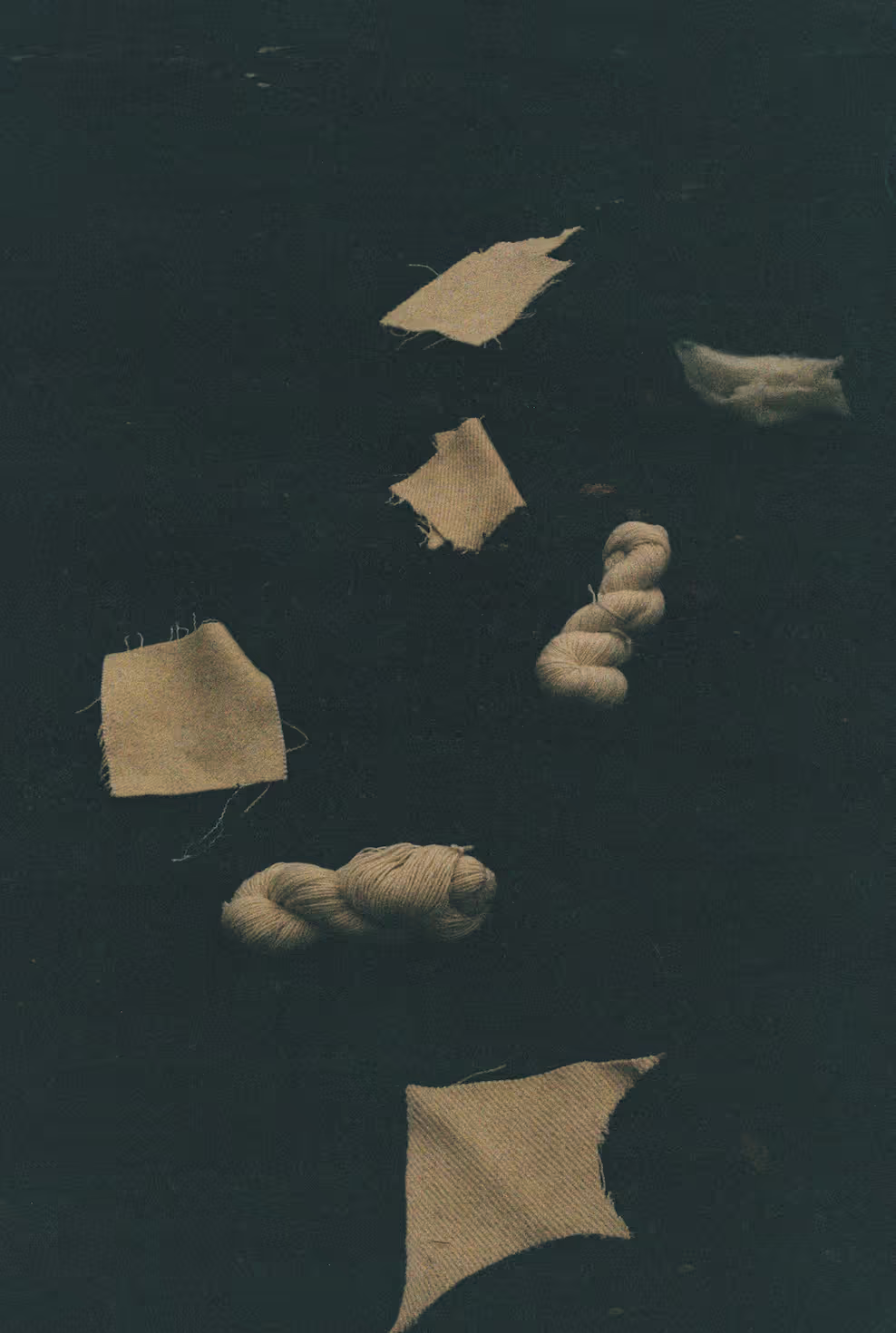

Yes, circularity is a natural phenomenon, and I see my work as part of that cycle — my products shouldn’t contradict it. I don’t use chemicals that would damage the wool fiber’s structure. Wool thus retains its natural components — nitrogen, carbon, and other elements.

This brings some limitations — garments mustn’t be washed with aggressive detergents, which would harm the fiber. On the other hand, it has major advantages. If treated correctly, the fiber stays “alive,” continues to work, and requires very little care — often just airing outdoors is enough. Raw wool fiber can regenerate itself thanks to air humidity. It breathes. It lives.

At the end of a garment’s life cycle, polyester threads must be removed. Unfortunately polyester is still irreplaceable — no other thread has the required strength. But once removed, the garment can return to the soil and decompose naturally. More than that — it even acts as fertilizer, since it still contains nitrogen and carbon that enrich the soil. The cycle closes again. In healthy soil, new life emerges.

What limits do you encounter as a small-scale local producer?

Some limitations come from industrial processes, others I impose on myself by insisting on doing as much as possible by hand. That means production volume is partly determined by how much wool I can sort manually.

The quantities I work with are limiting in another sense too — I have to purchase larger amounts of raw material. That’s demanding both financially and practically — even just finding space to store rolls of fabric is a challenge. For me, what already feels overwhelming is, for factories, far too little. They’re used to working on a completely different scale. So I have to seek compromises and ways of working together — so that it makes sense financially for both sides.

Right now I’ve slowed down production. Doing everything myself makes it very hard to cover the whole scope: clothing production, cutting yardage for customers, packaging orders. I’m reassessing my work and product range.

What role does collaboration play in your work?

I’m open to all forms of collaboration. What I do — working with wool — is part of my lifestyle. It’s not just about dressing myself and others sustainably. It’s everything around it; it’s essential. My lifestyle is built on self-sufficiency and connection to nature, but everything I create is also the result of collaboration.

Wool passes through many hands — not only mine. A shearer must come, clip the sheep, and the fleece then goes on to washing, spinning, weaving, and fulling. Without these facilities my work wouldn’t be possible. But collaboration can also be complicated — sometimes trust doesn’t pay off.

For me it’s essential that my products remain sustainable and free of chemical additives. That always comes at the expense of profit — which is, of course, the central value in capitalism. I too have to earn a living, for both my brand and my farm, but in a way that makes sense.

What are you working on at the moment? Is there something you’re trying to refine?

I still see many ways my textiles could be improved. Right now I’m focusing on making them thinner, softer, and more drapable, so I’m looking into new machines and techniques.

Alongside that, I’m working with a Czech company on a new project — making wool hats, which should be ready by winter. And a big development for early next year is opening a studio on my farmstead. We’re building it ourselves — with my father — using timber from our own forest, processed on site. It’s time-consuming, but meaningful.

Responsible fashion tends to have a distinctive aesthetic. Is that a barrier in terms of mainstream taste? How do you deal with it?

I think mainstream taste is a topic of its own — and that kind of clientele doesn’t usually come to me. I work slowly and put a lot of emphasis on my design input in each garment or object I make. I work with clean lines, because wool can often appear raw, so I counterbalance that with simplicity and a minimalist approach to ornament.

As a result, my products fall into a different price category compared to other local wool goods, and that attracts a different type of customer.

In the past, you created clothing for shepherds. Do you still do that?

I have to laugh. I’d like to, but those garments are so durable that they’re still in use — no need for new ones. Maybe someone will ask again one day.

What other qualities and uses does wool have, beyond fashion?

Wool is amazing for maintaining indoor climate. It absorbs moisture and gradually releases it depending on the temperature. The same goes for body temperature: wool garments cool in summer and warm in winter.

Today our interiors are filled with heavy chemicals — scents, cleaning agents, furniture glued with formaldehydes. Wool absorbs these and helps keep our environment clean and balanced. Used for tapestries, rugs, or decorative cushions, it supports a healthy home.

Another use is fertilizer. Not all wool is suitable for textiles. For example, wool shorn around the belly or backside is basically waste. Some companies here are already making granulated fertilizer from wool, but it can also be used raw. I use it on tomatoes — it holds moisture and slowly releases it, so the plants need less watering, while the nitrogen and other nutrients feed them. Wool simply belongs in nature.

What are the biggest challenges for Czech wool today, and how can they be addressed?

Local wool is experiencing a renaissance. The field is developing quickly, as people have realized Czech wool isn’t such a bad material — and there’s plenty of it. If we understand each breed and process the wool properly, the result can be a truly high-quality, beautiful product.

I also see a trend among students, who are returning to Czech wool and traditional processing. I think larger companies will soon take it up as well. But that may bring challenges with suppliers, who could exploit wholesale prices for raw wool. That could be a problem.

Subsidies for sheep farming are relatively high today. Ideally, though, farming should be self-sufficient, with farmers valuing wool and other products properly. While subsidies do support exemplary farms, I also see some flocks that don’t live up to that support. In many ways, we have to relearn our relationship with natural materials, the land, and nature itself.

Johana Felixová (*2001) is a student at the Department of Theory and History of Art, UMPRUM, Prague.