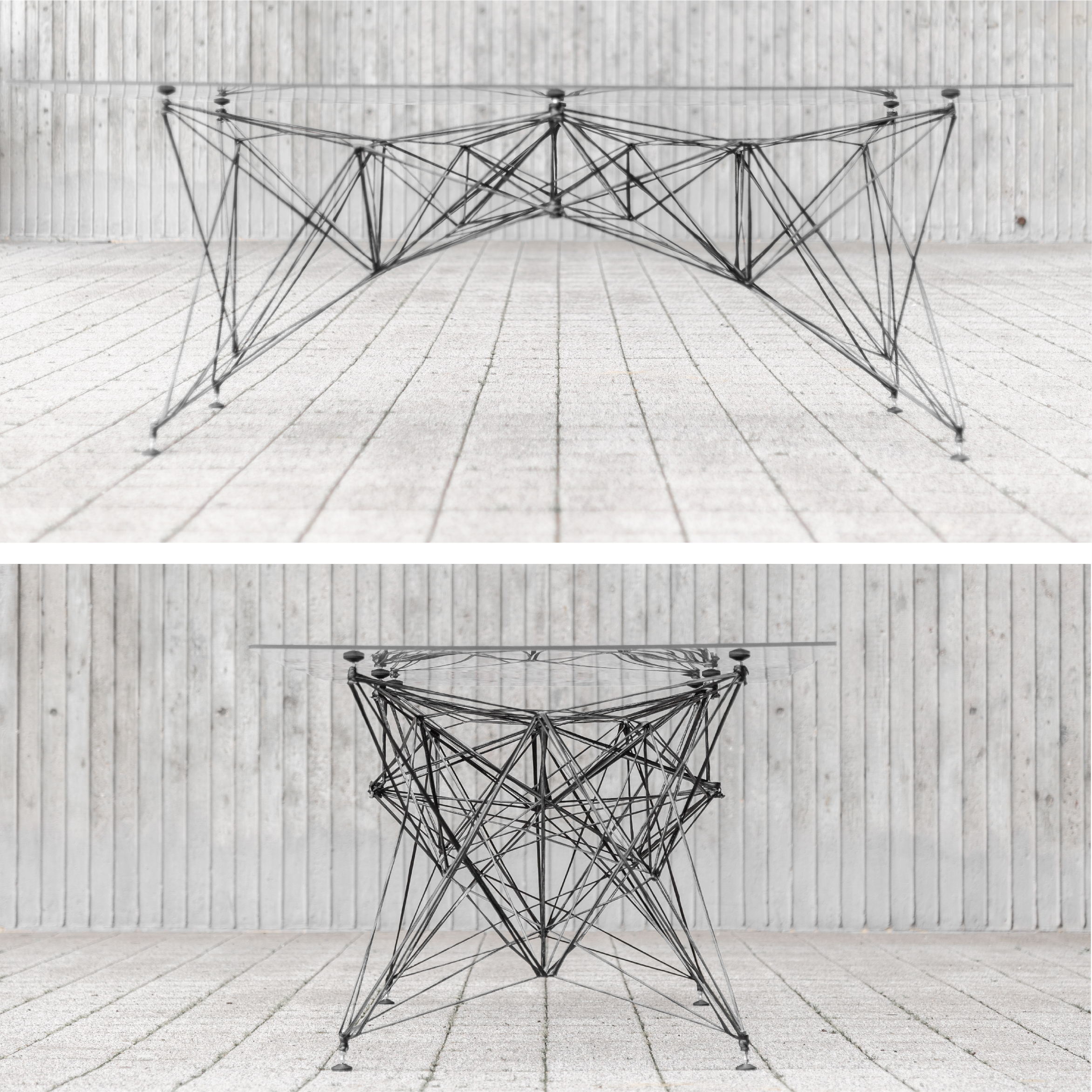

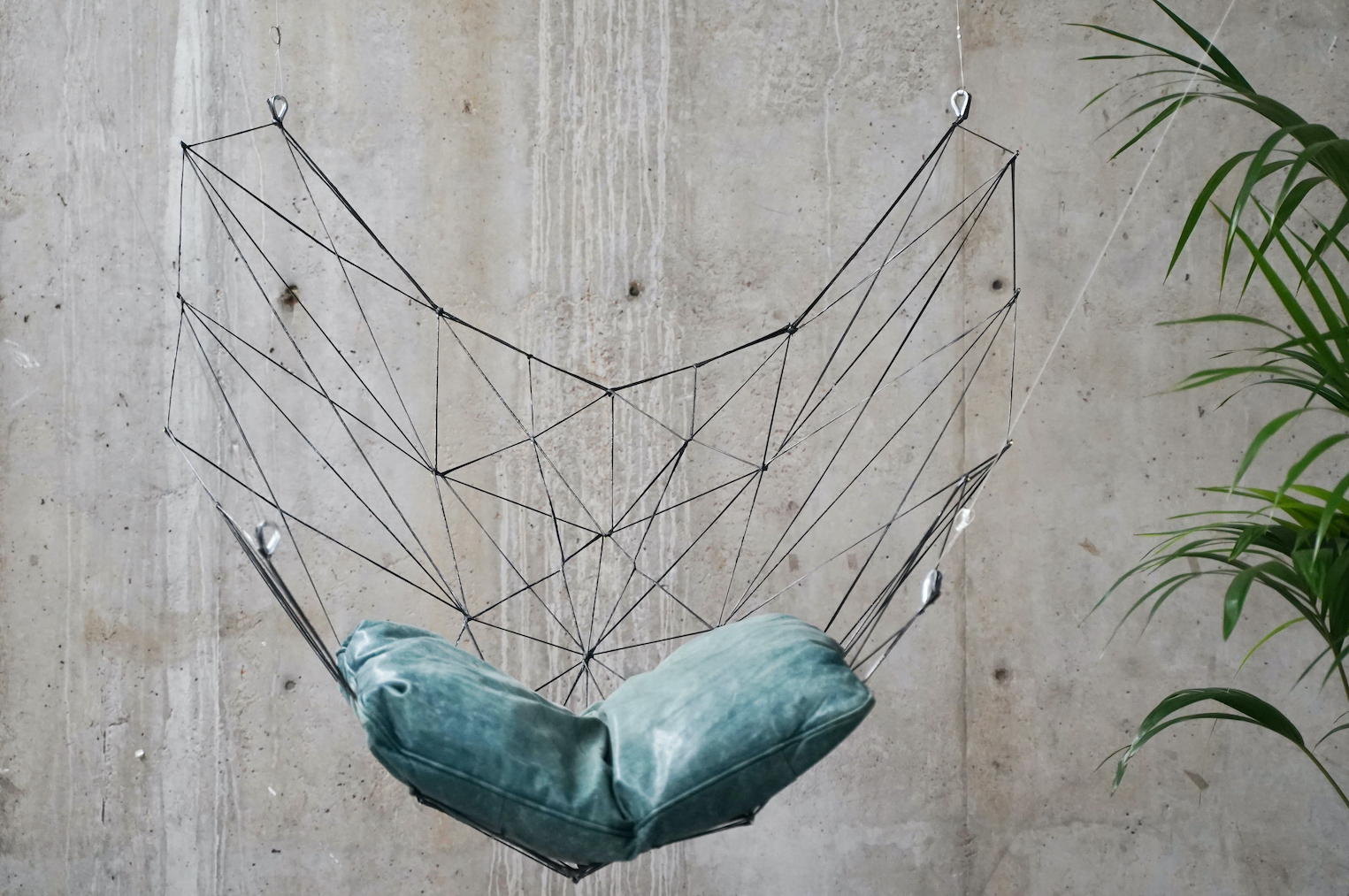

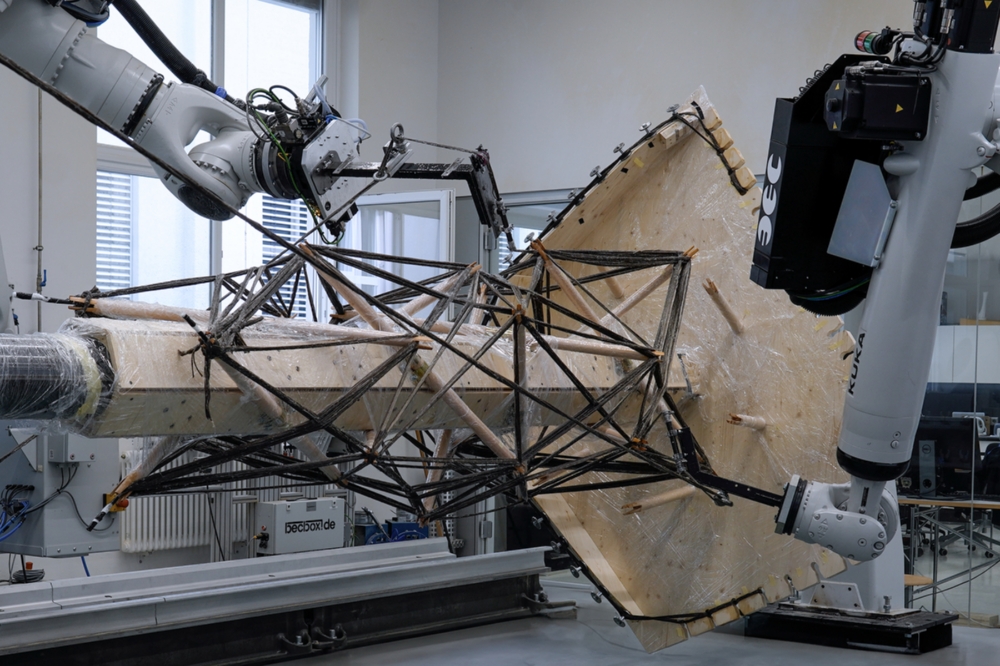

They have contributed to a number of projects that challenge conventional notions of material and construction, including Maison Fibre, a pavilion made entirely of fibers for the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021. Their most recent projects include the ITECH Pavilion (2024), developed with students on the campus of the University of Stuttgart, and The Hybrid Flax Pavilion (2024) in Wangen im Allgäu, Germany. Both projects present a hybrid building system combining timber with flax-fiber structures, leveraging the compressive strength of wood and the tensile and shear capacity of fibers. The fibers are robotically wound without the use of a mold, with the resulting geometry emerging from their material interaction. This combination significantly reduces material use while maintaining structural performance, and the system is designed so that its components can be easily disassembled, recycled or reused. Rebeca’s work also includes experimental furniture design, such as Aerochair and the spatially wound table, both are inspired by how a spider web is built.

WHAT FIRST INSPIRED YOU TO WORK WITH FIBROUS MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES?

My first contact with fibers was as a student in the ITECH Master's program. The topic of the first year design studio, which normally culminates in the design and fabrication of a research pavilion, was fibers, and I had a chance to dive into this material system for a year. Then, for my master's thesis, developed in the second year of the master's, I decided to work with fibers as well and keep building my material intuition in this area. I have always liked drawing and felt a strong connection to lines and their geometrical possibilities. When I came into contact with fibers as a building material, it felt as if I could transform the 2D lines in a drawing into a three-dimensional form in space. This inspired me to pursue a different direction for my thesis, and that's how Spatial Winding emerged. I wanted to manipulate the material as a continuous set of lines in space. Another aspect that really drew me to fibers was the way we can manipulate them with our hands. While I'm manually winding to create the spatial structures, I feel we are performing a choreography, and each hand movement can alter the final fiber structure. There is a lot of room for negotiation, and fibers are very forgiving.

IN NATURE, MOST STRUCTURES ARE COMPOSED OF FIBRES, WHOSE PROPERTIES DEPEND NOT ONLY ON THE STRENGTH OF THE FIBRES THEMSELVES BUT ALSO ON THE WAY THEY ARE ARRANGED. THIS ALLOWS FOR THE CREATION OF BOTH SOFT AND FLEXIBLE AS WELL AS EXTREMELY STRONG STRUCTURES. IN YOUR PROJECTS, FIBRES ARE NOT MERELY A PASSIVE MATERIAL BUT BECOME THE DRIVING FORCE OF THE ENTIRE DESIGN AND FABRICATION PROCESS. HOW DO YOU WORK WITH FIBRES IN THIS WAY?

The main property that guides the design of fiber structures is called anisotropy. It means that the mechanical properties of this material are dependent on the directionality of the fibers. During the design process, you will want to align the fibers with the main direction of forces, thereby improving force transmission along that direction. Another important design aspect is geometry: how you want to form your final structure will depend heavily on what can be formed with a continuous linear material. Since we mainly use a process called coreless filament winding, the fibers are not constrained by a mold. In this case, they are wound around anchor points fixed to a temporary frame, and the geometry emerges from the fiber's winding around these anchors and the material interactions that result from this process. So the definition of the boundary where the anchors will be placed and the anchors to be connected need to somehow enable fibers to touch. Understanding what works and what doesn't comes with practice, including a lot of physical and digital prototyping.

WHAT LED YOU AND YOUR COLLEGUES FROM THE FIBER ARCHITECTURE TEAM TO USE FLAX INSTEAD OF CONVENTIONAL TECHNICAL MATERIALS SUCH AS CARBON OR GLASS FIBRES, COMMONLY USED IN DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION? AND WHAT IS THE EXPECTED LIFESPAN OF FLAX FIBRES IN YOUR ARCHITECTURAL APPLICATIONS?

The main reason to shift towards bio-based fibers was the high environmental impact of carbon and glass fibers, as well as the difficult end-of-life scenarios they pose. With the pressing need to change the way we build and design, natural, renewable materials are a powerful strategy to reduce the impact of the built environment. So our team took on the challenge of investigating natural fibers, specifically flax, which offers the most favorable mechanical properties for structural use, grows very quickly (around 120 days), and is produced close to Germany, mostly in northern France. It took us a while to adjust our design and fabrication processes to accommodate this new material. In parallel, we have been working closely with industrial partners and fiber producers, and we have seen a great increase in options and in the quality of the flax fiber rovings we use since our first project. I believe this close collaboration between academia and industry is key in pushing the boundaries of what we can build and the materials we use. The more we demonstrate their potential, the greater the industry's interest in developing new, more sustainable materials. Regarding the lifespan of flax fibers in architectural applications, we are still investigating this. With the Hybrid Flax Pavilion, our first permanent building with a hybrid timber-flax roof, we have the opportunity to monitor its behavior and durability over an extended period. We hope to gather important information from this project, including the long-term behavior of the fiber element, which was impossible to obtain with temporary research pavilions. THE MATERIAL YOU WORK WITH IS NOT

ENTIRELY NATURAL, YET IT IS PREDOMINANTLY BIO-BASED, COMBINING FLAX FIBRES WITH RESIN. WHAT PROPORTION OF THE MATERIAL IS MADE UP OF FLAX, AND WHAT OTHER ADDITIVES DOES IT CONTAIN?

That's true; for structural use, the matrix we use is mostly petrol-based epoxy resins and hardeners, due to their improved mechanical properties. But since we shifted to natural fibers, we have also been investigating alternative natural matrix systems. For the Hybrid Flax Pavilion, we conducted an extensive comparison of different systems and identified a partially bio-based resin with great potential. However, their short pot-life didn’t work with our enclosed impregnation system, and we had to use epoxy for this project. Fortunately, in our parallel project, the ITECH Research Pavilion 2024, in which I was involved as a tutor, our impregnation system was based on an open resin bath system, and we managed to use it. It was the first time using a partially biobased resin system, in this case, with the hardener, which has 39% bio-based content, and it worked really well. We are also starting new partnerships with companies developing fully biobased matrix systems, with the hope of finding more sustainable alternatives for our future projects. The fiber-to-resin ratio will vary from project to project. Structural feedback will define a desired ratio, and the impregnation strategy during winding will then aim to achieve this value. With carbon, we could achieve a fiber mass ratio (FMR) of 55%, whereas with flax, it is around 42%. But again, these values will be highly case-specific. Regarding other additives, it will depend on the selected resin system. When working with epoxy resin, we normally keep the composite to fiber, resin, and hardener. In specific cases, if the fibers are exposed to direct sunlight, a UV protective additive can be used to prevent UV-induced polymer degradation.

HOW DO THE PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF FLAX — SUCH AS STRENGTH, ELASTICITY, OR TEXTURE — FACILITATE YOUR WORK AND IN WHAT WAYS DO THEY COMPLICATE IT?

In our first project with flax, the LivMats pavilion, the fiber rovings we had available had a low strength when dry and would break easily under the tension of the robotic arm during winding. To solve it, we used a twisted sisal roving with higher strength to be pulled together with the flax, so during fabrication, the sisal helped the flax to support the high tension applied by the robot, and avoid breakage. Currently, we work with two types of rovings with improved properties that allow us to wind without the sisal roving. One of them, from the French company Safilin, has a low twist, and the other, from the also French company Terre de Lin, is lightly wrapped by a thin cotton thread that keeps the fibers together and increases its strength during fabrication. Another important factor is that natural fibers absorb moisture, and water and epoxy resin don't get along. So we need to make sure our fibers are dry when we wind, to improve bonding between the fibers and the resin.

HOW DO YOU VIEW THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TRADITIONAL FIBRE-PROCESSING TECHNIQUES (SUCH AS HAND WEAVING OR KNITTING) AND DIGITALLY CONTROLLED ROBOTIC FABRICATION OF THREE- DIMENSIONAL STRUCTURES?

For all of our built projects, the manual prototyping will then later be replaced by the robotic process. While the manual manipulation gives you an initial understading of the material behavior and informs the design process, helping you to refine the final fiber pattern, the robotic process guarantees a more homogeneous material deposition, higher tension and the task of knowing where to wind the next fiber segment, what in the manual process might become quite labor intensive and complex depending on the amount of anchors points and the syntax logic. I think in the manual, traditional techniques, we can see something similar. While manual weaving and knitting processes are used for building experience and testing or even producing small pieces, when you need to rely on repetition and mass production, or even just a bigger piece, you move to industrial processes.

IN YOUR RESEARCH, THERE HAS BEEN A GRADUAL SHIFT TOWARDS WINDING FIBERS WITHOUT THE USE OF A RIGID FRAME. WHAT HAS THIS SHIFT BROUGHT IN TERMS OF NEW DESIGN POSSIBILITIES, BUT ALSO LIMITATIONS?

The simplification of the frame has been a general focus in this field to reduce costs and material use, and to streamline the pre-winding process as much as possible. But for me personally, it became almost an obsession (a healthy one, of course =)). For my master's thesis, Spatial Winding, it became a big part of the concept: what can I achieve by simplifying the frame to the bare minimum? What happens when the fiber itself becomes a support for the next fiber? These questions really shaped the path of this project and enabled us to expand the design space of fiber structures, developing a very lightweight spatial structure by going above, under, and around the already wound fibers. After that, I supervised different master's theses that followed the same objective. Pushing the boundaries of what was possible from a geometrical and fabrication point of view further and further. As for limitations, I would say the robotic fabrication can become quite tricky. In the case of Spatial Winding, you need two robots to exchange material and enable the “going around“ motion. This made the whole fabrication process much more complex than a normal winding logic. In the latest ITECH Research Pavilion 2024, I had the opportunity to investigate this even further with our students by using the timber itself as a frame and structure. In this case, there was no more steel frame with several anchor points, but designed timber joints to be directly wound on and permanently interface with the fibers. It was an amazing experience to co-develop this, and I see a lot of potential for future work.

THE HYBRID FLAX PAVILION DEMONSTRATES THAT BIO-BASED MATERIALS CAN FUNCTION AS FULLY VIABLE BUILDING MATERIALS. DO YOU SEE FLAX BECOMING A STANDARD STRUCTURAL MATERIAL IN FUTURE ARCHITECTURE, OR IS IT MORE LIKELY TO REMAIN WITHIN THE REALM OF EXPERIMENTATION?

Fiber-reinforced plastics had a first go in architecture in the 50’s with houses made of glass fiber panels, representing a very futuristic path with free-form geometries. However, these materials never really found their way as a main structural material in the construction sector. Flax composite has been gaining traction, especially in the automotive and aerospace industries. Mostly in non-primary structural components, where their low weight, good stiffness, vibration damping, and sustainability are quite attractive. Our research has increasingly shifted toward real architectural applications. I believe that closer collaboration with industrial partners, and potentially architectural practices, significantly increases the chances of implementing this material into built projects. Equally important is the standardization and expansion of building codes to accommodate non- standard materials such as flax. The more regulated and recognized these materials become, the more likely architects and engineers are to adopt them in practice.

HAS YOUR WORK WITH NATURAL MATERIALS INSPIRED SOMEONE IN YOUR PROFESSIONAL ENVIRONMENT TO MAKE A SIMILAR SHIFT?

I see this shift toward biomaterials becoming increasingly common. Given the urgency of replacing high-impact, non-renewable, petroleum-based materials, I hope our work can encourage others to pursue similar directions. One particularly meaningful experience in this regard was our collaboration with an industrial partner on the fabrication of the Hybrid Flax Pavilion roof elements. The company was specialized in carbon-fiber composites and, to work with us, had to adapt both their production equipment and process logic to flax. Through this project, they gained hands-on experience with the material and can now include flax in their portfolio, hopefully enabling and inspiring future projects to be built with it.

WHAT ROLE DOES CHANCE PLAY IN YOUR WORK, DOES IT EVER INFLUENCE THE DEVELOPMENT OF YOUR WORK, OR DO YOU TRY TO HAVE THE ENTIRE PROCESS FULLY UNDER CONTROL?

I think control is a particularly interesting concept in our field. With computational design and robotic fabrication, one can move toward total control, achieving extreme precision and very low tolerances, or toward the opposite extreme. Concepts such as emergent design and behavioral fabrication typically align with this latter approach. In these strategies, the design process is entrusted to a set of parameters and logics, or to the materials’ and robots’ responses to real-time conditions during fabrication. I find this approach especially fascinating and have been coteaching the seminar Behavioral Fabrication in the ITECH master’s program since I began my position as a research associate at ICD in 2019. In the case of fibers, experience teaches you to respect the material. And with that, you start to understand when to let the final outcome be shaped by it. Control is maintained primarily at the level of design intent, while during fabrication, it is reduced to essential aspects, such as ensuring that anchor points connect correctly. In the fabrication of Maison Fibre, the project we developed and built for the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021, it was crucial that all slab and wall elements fit together accurately. We therefore developed specific strategies to ensure consistent boundary dimensions and precise alignment of anchor points during assembly. In the end, the approach proved highly effective, and the assembly process was smoother than expected.

WHAT ARE YOU CURRENTLY WORKING ON? DO YOU PLAN TO EXPERIMENT WITH OTHER NATURAL MATERIALS BESIDES FLAX AND TIMBER?