► českou verzi článku najdete zde

As the co-founder of the sustainable startup project “sålidt” I know how product development can serve as a catalyst for a really good idea. Sålidt promotes packaging-free cosmetics – specifically bar soaps and shampoos. In the future, we also want to supplement this by offering accessories for easy storage and transportation. These will be produced from recycled plastic packaging. We also plan to create non-plastic-based varieties. The aim is to help bring attention to the problem of excessive waste packaging generated by liquid shower gels and shampoos, as well as the environmental issues associated with the current state of affairs. Additionally, we also want to highlight the excessive use of chemical additives in such products.

The development process often requires tough decisions to be made. For example: what materials should be used, or which cosmetics supplier should be chosen? And how best can consumers be motivated to change established habits, and how can they be persuaded that new and different choices exist with regards to personal hygiene products? A lack of available information about the environmental impact of given materials is one issue. Then there is the ability to reshape the existing systemic structures, which complicate and thwart our efforts. What is the best way to build up regional supply chains? And how can one reduce the volume of packaging materials, while still adhering to legal requirements for the storage and transport of products? Naturally, such factors are all ultimately reflected in the end price of goods. So how to withstand tough competition in light of all this? And finally, how to persuade pampered consumers that there is a viable option that avoids all that single-use plastic packaging?

Even during the product design phase, a number of relevant factors need to be considered. These include: the amount of time that a particular consumer product lasts; the possibility of product repair; and also how to dispose of a product at the end of its life. Solutions that consider both sustainability and limiting environmental impact must be generated at these stages. During the design phase of our bar soaps and shampoos we also factor-in issues pertaining to ease of storage and transport, thus easing their way into consumers’ bathrooms. Joseph Huber, a professor of environmental sociology, has described three indivisible principles of sustainability: efficiency, consistency and sufficiency.

Efficiency concerns itself with the issue of how to produce more from a given amount of materials – which means a more productive and targeted usage of natural resources. This not only pertains to improving individual production processes, but also the more efficient usage of already existing products, as well as limiting waste from these.

One example of this is the so-called “sharing economy”, which promotes the shared usage of products as a substitute to ownership. Familiar models along these lines, such as car or apartment sharing, can also be crafted along more personal parameters via the loaning or renting of items that would otherwise remain largely unused. The popularity of this trend is underscored by a number of Internet resources: in Toronto; Brussels, which among other things also operates a “tool library”; and in Germany the community “neighbour” platforms Nebenan and Ausleihbar-Kiel.

The second principle, namely consistency, pertains to placing an emphasis on structural changes in the kind of social, technological and political arenas which are required in order to attain equilibrium between our industrial and natural metabolisms. The principal of the circular economy is built upon this concept, and differs from the classic linear processes embodied in the “take, make, dispose!” model. A circular system is designed to arrange industrial processes and product creation in such a way as to enable maximum possible use and re-use, thus limiting to the greatest possible extent the production of waste materials.

This enables not only the closer monitoring of new materials, but also more efficient usage of those materials viewed in the past as of little practical use. As an example, sports clothing and shoe firm Adidas recently created a limited edition line of trainers, with 95 percent of plastics used in their manufacture retrieved as waste from the sea. Cosmetics producer Procter & Gamble is making a similar effort in terms of using plastic waste washed up on beaches, promising that by 2018, 90 percent of its plastic bottles distributed throughout Europe will contain 25 percent of such reclaimed waste plastics.

“Mashroom” packaging, courtesy of producer Ecovative, represents yet another example. In this case, however, packaging is literally created from fungal “mushroom materials”, which transform straw and other agricultural waste products into a light, resistant, and biodegradable material that can replace existing plastic products such as polystyrene. It is important that products and processes are proposed in such a manner as to make their biological and synthetic components reusable. Ideally, artificially created synthetic products should be used as part of a so-called closed circuit involving proper disposal and recycling. But non-toxic biological materials can simply biodegrade back into the natural environment, and can, for example, be used as compost.

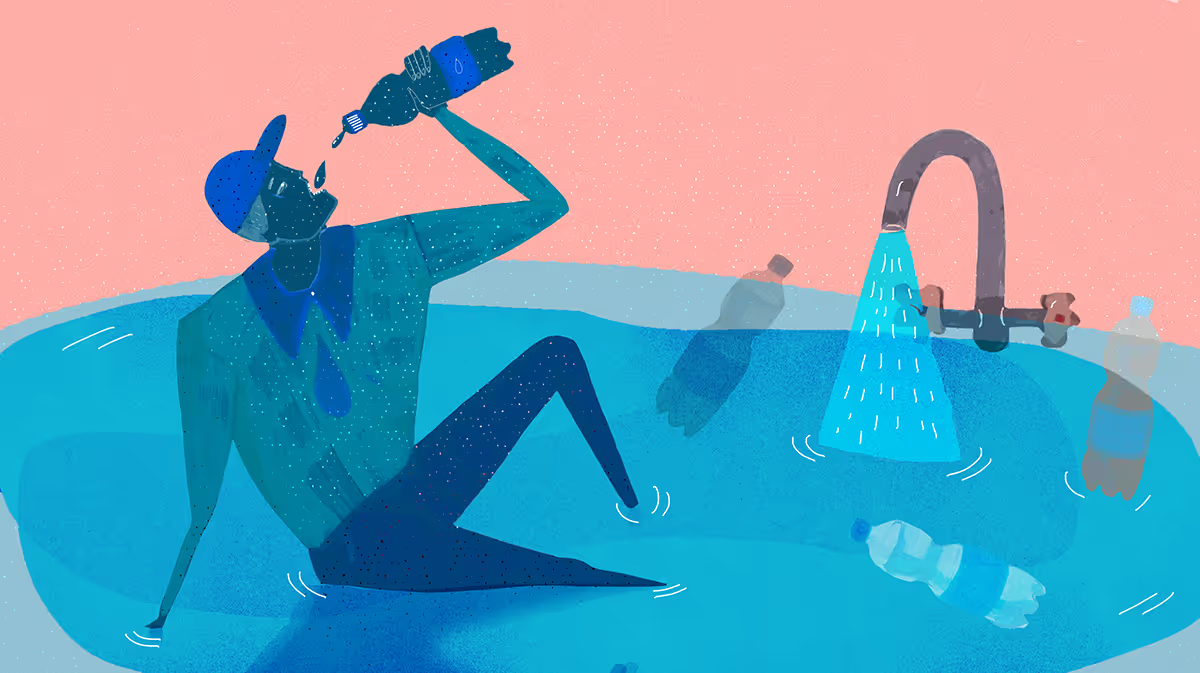

The third principle – sufficiency (adequacy and ampleness) – provides solutions for the social dimension. This includes tackling social norms, and also promoting disengagement from materialist practices via voluntary minimalism. This involves urging shoppers to shun unfettered consumerism with its endless cycle of sales, discounts, single-use disposable products, and planned obsolescence… It does not, however, mean promoting austerity and poverty, but rather a conscious exploration of just how many material possessions we really need for a comfortable life, and how this contrasts with what marketing and advertising claims that we need.

Increased support from consumers for environmentally and socially responsible products is, in turn, leading to a wider transformation of existing standards and practices. Because through our purchasing choices we are sending a clear signal that we are aware of a company’s practices, and that demand exists for further products produced along similarly responsible lines. Conversely, it also means that each product purchased which fails to adhere to current environmental and ethical expectations will fuel the production of yet more of the same – meaning no pressure for change.

Naturally, the three aforementioned strategies are mutually interdependent. According to Professor Hubert, the attainment of sustainable development requires the concurrent institutionalisation of all three. But how to achieve this? Appropriate designs are a key factor in such principles being effectively put into practice. The ascent of sustainable development is also leading to an elevation of the status of designers to positions of paramount importance. Not just in the development of new products, materials, services and processes, but their work is also crucial with regards to supporting social innovations, and formulating new social practices related to the usage of particular products.

Design is something that should be viewed holistically – meaning not merely pursuing economic interests, but also factoring-in environmental impact, and concerning oneself with where, and under what conditions, products are made. Also from where necessary materials are sourced, and what happens to products at the end of their useful lives. All of the above is something that designers must today consider.

There are those who might view such concepts as unrealistic or unattainable. And a clear conflict between economic and environmental interests would appear, on the surface, to preclude progress in this field. But new ways of doing business could serve to provide a solution. For example, the Czech startup Infiberry has developed a reusable alternative to plastic bags. The functional fabric made from polylactic acid is sufficiently resilient and light to be used in this manner, and is also biodegradable. The colourful bags, known under the Frusack brand name, are helping to motivate consumers to reduce the kind of waste generation associated with single-use plastic bags.

German tea seller Teekampagne distributes high quality loose leaf teas, in 500g or 1kg packaging, direct from tea plantations. The elimination of unnecessary middlemen in the distribution chain means the firm can offer its goods at a favourable price to customers, while also ensuring a significantly higher revenue for plantation workers. And it, too, is successfully reducing excessive packaging.

A new generation of socially responsible producers is coming to the fore. Battling for their place in the market, such visionaries are able to assemble both the necessary material and immaterial resources. They are also willing to accept the risks associated with such entrepreneurial endeavours. Thorough planning and highly innovative business models, built on principles of respect, solidarity, and preserving environmental resources, offer such entrepreneurs a chance to actively compete in the marketplace. Asides from generating responsible profits, business must be viewed as a means by which additional benefits are also created for a broad spectrum of interested parties.

Kristýna Jaklová is currently completing her studies in the international Sustainable Development graduate programme in Germany. Her master’s thesis examines alternative methods of doing business. These combine economic self-sufficiency and reducing environmental impact. Such practices also contribute towards the cultivation and consolidation of positive environmental and social values. Asides from this, she is also working on her own project entitled “sålidt”. The project has gained a scholarship grant from the Leipzig-based Social Impact Lab. She has also gained backing from Climate-KIC.